A popular song in choir repertoires, “Betelehemu” is a Yoruba Christmas carol by the Grammy-nominated drummer Babatunde Olatunji, arranged for men’s choir by Wendell P. Whalum. It came into being while Olatunji was a student on scholarship at Morehouse College in the 1950s: he shared it with Whalum, director of the school’s glee club, and that spawned a collaboration.

There have been numerous recordings of “Betelehemu” over the years, and each one has its own distinct flavor, especially in the percussion sections. I really like the one by The Young People’s Choir of New York City from the 2003 album It Is Possible. But here’s a version from Brazil, arranged for SATB by Jonathan Crutchfield:

You might also be interested in performances by the Morehouse College Glee Club (from their one hundredth anniversary concert in 2012) and the African Children’s Choir.

Here are the Yoruba lyrics and English translation to follow along with, provided courtesy of my friends Ezekiel Olagoke and Temidayo Akinsanya. For a pronunciation guide, click here.

Betelehemu

Awa yio ri Baba gbojule

Awa yio ri Baba fehinti

Nibo labi Jesu

Nibo labe bi i

Betelehemu, ilu ara

Nibe labi Baba o daju

Iyin, iyin, iyin nifun o

Adupe fun o, adupe fun o, adupe fun ojo oni

Baba oloreo

Iyin, iyin, iyin fun o Baba anu

Baba toda wasi

Betelehemu

Bethlehem

We shall see that we have a Father to trust

We shall see that we have a Father to rely on

Where was Jesus born?

Where was he born?

Bethlehem, the city of wonder

That is where the Father was born for sure

Praise, praise, praise be to Him

We thank You, we thank You, we thank You for this day

Blessed Father

Praise, praise, praise be to You, merciful Father

Father who delivered us

Bethlehem

The lyrics are simple, rejoicing in the Father’s glory and grace in giving his Son over to be born in Bethlehem. I asked my Yoruba friends about the line “That is where the Father was born for sure,” which seems problematic from a Trinitarian perspective, because it was the Son, Jesus—not the Father—who was born in Bethlehem. The Yoruba word Baba has more nuance than the English “Father”; it is used to signify a biological relationship but also as an honorific for wise men or elders. But still I wondered whether it is theologically appropriate.

Ezekiel told me that Yoruba Christians understand the distinctions between the three persons of the Trinity and that Baba is not commonly used to refer to Jesus, but in defense of it, he pointed me to scripture passages like Daniel 7:9–14 (cf. the book of Revelation), which describes Jesus as “the Ancient of Days”; John 8:58, in which Jesus tells his disciples, “Before Abraham was, I am,” ascribing to himself a status greater than that of the greatest Jewish patriarch; and Colossians 1:15–17: “He [Jesus] is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him. And he is before all things, and in him all things hold together.” In Yoruba culture and other African cultures as well, says Ezekiel, Jesus is sometimes called “Chief” or “Ancestor,” a similar notion that emphasizes his being before all things, the eternal Source in whom all things consist.

Temi said that to avoid confusion, he would probably recommend a revision from Nibe labi Baba o daju to Nibe labi Jesu o daju (or else he’d drop the name so that the indefinite pronoun “he” is implied instead).

Both friends felt that the phrase Awa yio ri (“We shall see”) in the second and third lines is awkward in this context. All the other lyric translations I’ve found translate the phrase as “We are glad,” but that would be Awa ni, Ezekiel said—and that doesn’t quite fit the musical meter. It’s possible that the song is merging Advent with Christmas: it starts with looking forward to the birth, then it acknowledges the birth as having happened, eliciting appellations of praise.

It seems that “Betelehemu” is more popular outside Nigeria than in. Ezekiel and Temi and one other Yoruba friend (from different generations) said that despite growing up in Christian homes in Nigeria, they’ve never heard it before, but they’ve heard ones similar to it. So while some sources credit “Betelehemu” as a “Yoruba folk text” and “Yoruba folk tune,” leaving Olatunji out entirely, I think it’s more likely that Olatunji drew on the song traditions of his people to create a new composition. At the very least, Olatunji introduced the song to the United States—and our Christmas concerts are all the richer for it!

+++

Babatunde Olatunji (1927–2003) was born and raised in Ajido, a fishing and trading village in southwestern Nigeria, as a member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Upon receiving a Rotary scholarship in 1950, he moved to the United States with dreams of becoming a diplomat. While studying political science at Morehouse, he was astounded by how little his classmates knew about Africa:

They had no concept of Africa. They asked all kinds of questions: “Do lions really roam the streets? Do people sleep in trees?” They even asked me if Africans had tails! They thought Africa was like the Tarzan movies. Ignorance is bliss, but it is a dangerous bliss.

Africa had given so much to world culture, but they didn’t know it. I decided to educate my colleagues about Africa, so I would invite them to my room and we would talk about their African heritage. We’d listen to blues on the radio and I’d say, “That’s African music!” One television program we watched was I Love Lucy. Ricky Ricardo would sing, “Baba loo, aiye!” That is a Yoruba folk song from Nigeria! It is sung by newlyweds and it says, “Father, lord of the world, please give me a child to play with.” (qtd. by the Percussive Arts Society)

Olatunji taught his fellow students some of the rhythms, songs, and dances of his native land and even organized performances.

After graduating from Morehouse with a bachelor’s degree, Olatunji went on to New York University to study public administration. During this time he organized a small drum and dance troupe and began giving school programs on African cultural heritage, which he loved so much that he made it his vocation: education and performance. His performance with the Radio City Music Hall orchestra in 1958 led to Columbia Records signing him to their label, under which he released six albums. His first one, Drums of Passion (1960), was a major hit, selling over five million copies. Widely credited with popularizing African music in the West, it was added to the United States’ National Recording Registry in 2004.

Olatunji performed and/or recorded with many other prominent musicians throughout his career, including John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderly, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Quincy Jones, Dizzy Gillespie, Stevie Wonder, Carlos Santana, and Mickey Hart (of the Grateful Dead), who said that Olatunji’s performance at his elementary school is what inspired him to pursue a career in percussion.

Teaching was always Olatunji’s priority: in 1965 he established the Olatunji Center for African Culture in Harlem, which offered music and dance lessons to children until 1984, when it closed for lack of funding.

For more information on Babatunde Olatunji, check out his posthumously published autobiography, The Beat of My Drum.

+++

Wendell P. Whalum (1931–1987) was an internationally recognized lecturer, organist, conductor, musicologist, arranger, composer, and author whose scholarship focused on the areas of hymnody and Negro spirituals. He was born and raised in Tennessee but made Atlanta, Georgia, his permanent home in 1953 when he began his thirty-four-year run as director of the Morehouse College Glee Club. Because he had a strong interest in quality church music, he accepted positions as organist-composer for several Atlanta churches: Providence Baptist Church, Allen Temple AME Church, Ebenezer Baptist Church, and Friendship Baptist Church.

+++

Between 1947 and 1954 several woodcarvings of Jesus’s birth narrative were made by Yoruba artists in a traditional style—as door reliefs and as crèches. That’s because during those years, a workshop was in operation in Oye, Ekiti, Nigeria, run by the Irish Catholic missionary Father Kevin Carroll, whose aim was to promote the development of an indigenous Christian art among the Yoruba people. Funded by the Society of African Missions, the Oye-Ekiti workshop provided materials, a work space, and commissions for local artists. Father Carroll taught the artists Bible stories and encouraged them to interpret them in light of their own cultural context—marking a decisive shift away from the Catholic Church’s then-predominant missionary practice of having indigenous artists copy European works of art.

In consultation with workshop artists, Father Carroll developed a painted prototype of the Nativity.

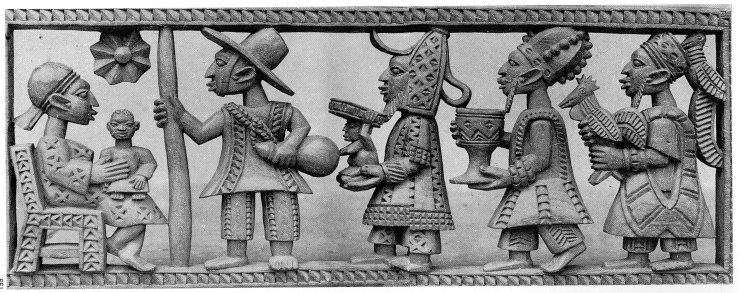

It shows the wise men clothed in the regalia of Yoruba obas—beaded crowns (ades) and embroidered robes. The first king comes bearing a rooster-shaped olumeye, a storage container for kola nuts; in Yoruba homes, these caffeinated treats are shared with guests as a gesture of hospitality and friendship. The second king brings an agere Ifa, used in Yoruba divination rituals to hold palm nuts; the base of the container is shaped like a bare-chested devotee.

Workshop artists likely referred to this painting when they produced a nativity set for the Vatican-sponsored “Exhibition of Sacred Art from the Missionlands” in Rome in 1950.

Delighted by this new Yoruba-Christian fusion, Archbishop (soon-to-be Cardinal) Celso Costantini commissioned a nativity set for himself, shown below.

The head carver on these was George Bandele (1908/10–1995), son of the famous woodcarver Areogun of Osi-Ilorin (1880–1954). Bandele was the Oye-Ekiti workshop’s most prolific artist and one of its most accomplished. Even after the workshop closed, he continued to receive commissions from Christian churches and institutions, as well as for traditional Yoruba religious, royal, and civic clients.

The carved door below by Bandele shown below (its original location is unknown) shows three scenes from the Christmas story: the Adoration of the Magi, the Annunciation, and the Flight to Egypt.

In the top register, the wise men approach with a live chicken for sacrifice, and two Yoruba offering vessels. In the middle register, Gabriel holds out a kola branch to Mary, who is hard at work pounding yams.

Another visualization of Jesus during infancy, from another door, shows him in the arms of his mother, Mary, and flanked by Adam and Eve, a reminder that Christ has come to redeem us from the curse of the Fall.

George Bandele apprenticed several woodcarvers during his career, including Lamidi Fakeye and Joseph Agbana. Fakeye’s door carving of the Presentation in the Temple shows Mary handing baby Jesus to Simeon while Joseph stands by with two turtledoves for the requisite sacrifice.

More recently, in 1997, Fakeye fulfilled a commission from Our Saviour Lutheran Church in West Lafayette, Indiana, to illustrate the life of Christ in a series of wood panel carvings. His Nativity panel shows Mary and Jesus as Yoruba and the shepherds as Hausa, Fulani, and Ibgo, neighboring ethnic groups.

In 1974, Joseph Agbana (some sources call him Joseph Imale) carved a nativity set for the Society of African Missions African Art Museum. Similar to the other Yoruba Christian nativities, it portrays the magi as Yoruba kings bearing traditional gifts.

The shepherds, who wear the cloths of Fulani herdsmen from northern Nigeria, also bring culturally appropriate gifts, carried under their left arms: a live chicken and a calabash of milk.

Joseph’s cap is embroidered in the style of the Muslim Hausa of northern Nigeria, and Mary’s dress is made of indigo tie-dyed cloth like that made and worn by Yoruba women. Her necklace of handmade glass beads was made in the town of Bida.

Here’s a Holy Family group by Agbana from a few years later:

And an Adoration of the Magi by Daniel Bamidele:

Iyin, iyin, iyin—praise, praise, praise! To Jesus, who was born in Bethlehem for all the world.

For more information on the Oye-Ekiti workshop and the issue of contextualization, see my review of the 2014 exhibition “Africanizing Christian Art.” For a wealth of African Christian art images—most in black and white but some in color—see the German tome Christliche Kunst in Africa by J. F. Thiel and Heinz Helf (1984). It’s out of print, but you can find it for sale via used-book e-tailers or could perhaps request a loan from your local library.

[…] (Related post: “Yoruba Christmas Carol and Art [Nigeria]”) […]

LikeLike